Photo by Plismo.

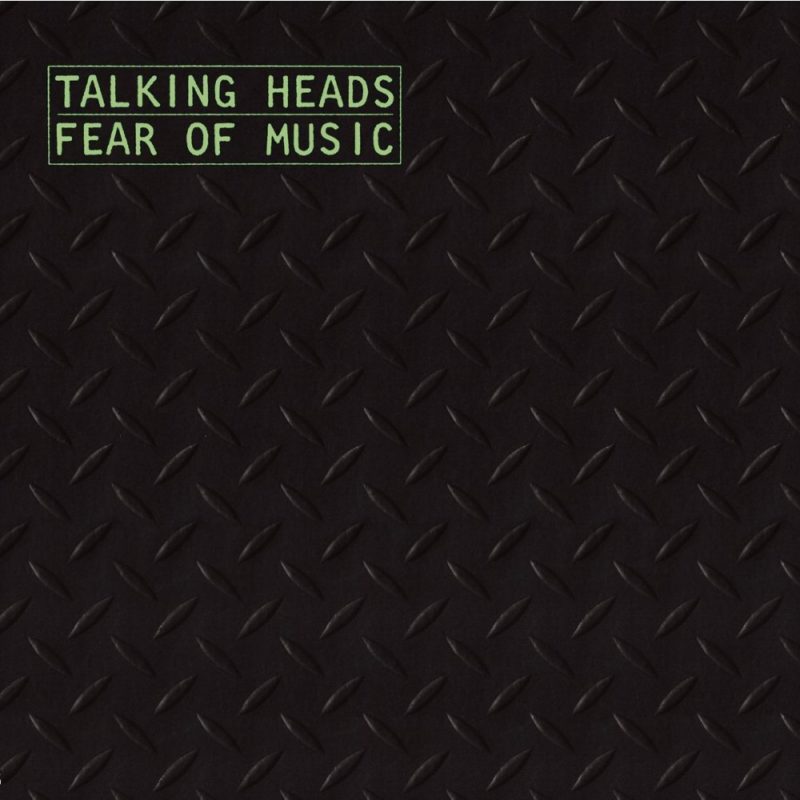

“Air can hurt you, too,” David Byrne sang on a record released forty years ago this month. The song was called “Air,” the album, Fear of Music, and the name of the band was Talking Heads. If one is to believe random internet commentary–claims often attributed to memory of some Byrne interview or another–this was not a song about air pollution.

No argument here. I would point out, however, that this song was made within a decade or so of the rise of modern environmentalism in the US, which was acutely attuned to the imagery of air that could hurt you–to photos of billowing industrial smokestacks and thick smog hovering over cities such as Los Angeles and New York. It was also a song recorded within weeks of the accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania when one the facility’s reactors suffered a near-meltdown, and radioactive gases were vented into the atmosphere.

Good songs resist being reduced to prosaic readings. “Air” isn’t about air pollution. But it is a song that draws on the ecological imagination, the shift in the way many perceive the nature of reality and their relations with their surroundings. It is a song that partakes of historical context and events in which the ecological imagination took shape. And it is a song that speaks to the fear and dread that is, to my mind, one of the under-explored and under-theorized aspects of that imagination.

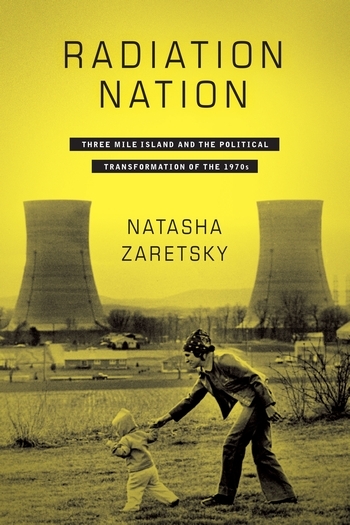

In her book Radiation Nation: Three Mile Island and the Political Transformation of the 1970s (Columbia UP, 2018), Natasha Zaretsky provides a case study in what I’ll call, for this post, environmental fear. The consciousness of our interdependence with the living world, our interconnectedness and our embeddedness in nonhuman life processes, is often associated with a commitment to universalism. When the Apollo photos, such as “Earthrise,” were published, people saw that they shared the same “lonely planet,” that we were all one, etc. But in the local response to the accident at Three Mile Island, Zaretsky reveals another aspect of the ecological imagination. To put it bluntly, the response was tribal. Trust, already weakened, broke down. In the end, universalist perspectives were rejected for the sort of resentment-based nationalism that we’re so familiar with today.

“What is happening to my skin?” Byrne sings. “Where is the protection that I needed?” The ecological imagination emphasizes the permeability of boundaries, not least skin boundaries. The fact that radiation poisoning was invisible and its effects gradual, for example, made it an especially insidious kind of bodily threat. The Three Mile Island community perceived itself, Zaretsky argues, as the heartland, as the true body of America. That body had been invaded. Sixties progressives had celebrated the body as a site of liberation and pleasure, but in the reaction to Three Mile Island, “conservatives folded the body into a discourse of decline and betrayal, creating a body politics of their own” (98). Zaretsky calls this “biotic nationalism.”

Some bodies were more vulnerable than others. Mothers, pregnant women, and children were the first advised to evacuate. In abstract terms, they represented what was most in peril–a society’s ability to reproduce itself. The symbols adopted by the movement came to reflect this. Biotic nationalism was “shot through with ecologically derived images of the vulnerable bodies of mothers, babies, and fetuses” (13). Meanwhile, within conservative politics more broadly, the rights of the unborn were likewise moving to the center of concern. Writing recently in Politico, Dartmouth’s Randall Balmer has stressed the role race played in this political restructuring. Having lost the moral high ground in the contest over segregation, social conservatives and evangelicals sought to reclaim it on the issue of abortion. In Radiation Nation, Zaretsky provides an ecological inflection to this more familiar story.

Some bodies were more vulnerable than others. Mothers, pregnant women, and children were the first advised to evacuate. In abstract terms, they represented what was most in peril–a society’s ability to reproduce itself. The symbols adopted by the movement came to reflect this. Biotic nationalism was “shot through with ecologically derived images of the vulnerable bodies of mothers, babies, and fetuses” (13). Meanwhile, within conservative politics more broadly, the rights of the unborn were likewise moving to the center of concern. Writing recently in Politico, Dartmouth’s Randall Balmer has stressed the role race played in this political restructuring. Having lost the moral high ground in the contest over segregation, social conservatives and evangelicals sought to reclaim it on the issue of abortion. In Radiation Nation, Zaretsky provides an ecological inflection to this more familiar story.

Zaretsky’s book tells us something about environmental fear politically. On this blog, I’ve written about Sarah J. Ray’s research into student distress over the climate crisis. All this helps. Still, I want to cast a wider net.

At first, “Air can hurt you, too,” seems a neurotic claim. It fits the twitchy, hyper-literal persona David Byrne had established with the group’s first two records. The song is less a warning about air than it is a warning about fear. Its underlying message–its wider inference in the Byrne program–is to push past fear and to embrace life’s wonderful messiness. The theme would become more direct in subsequent records. But the song’s conceit only works if the claims made about air are perceived as paranoid, which they aren’t, by any means. Air can hurt us. Millions die from dirty air every year around the globe, most especially in the global south, where our fossil-fuel-based economics tends to shunt its externalities. Would the song make sense at all in a place where people don surgical masks to go out of doors? These considerations push the song even further away from an environmentalist reading. Or we might put it this way: “Air” functions in a space of relative privilege.

At first, “Air can hurt you, too,” seems a neurotic claim. It fits the twitchy, hyper-literal persona David Byrne had established with the group’s first two records. The song is less a warning about air than it is a warning about fear. Its underlying message–its wider inference in the Byrne program–is to push past fear and to embrace life’s wonderful messiness. The theme would become more direct in subsequent records. But the song’s conceit only works if the claims made about air are perceived as paranoid, which they aren’t, by any means. Air can hurt us. Millions die from dirty air every year around the globe, most especially in the global south, where our fossil-fuel-based economics tends to shunt its externalities. Would the song make sense at all in a place where people don surgical masks to go out of doors? These considerations push the song even further away from an environmentalist reading. Or we might put it this way: “Air” functions in a space of relative privilege.

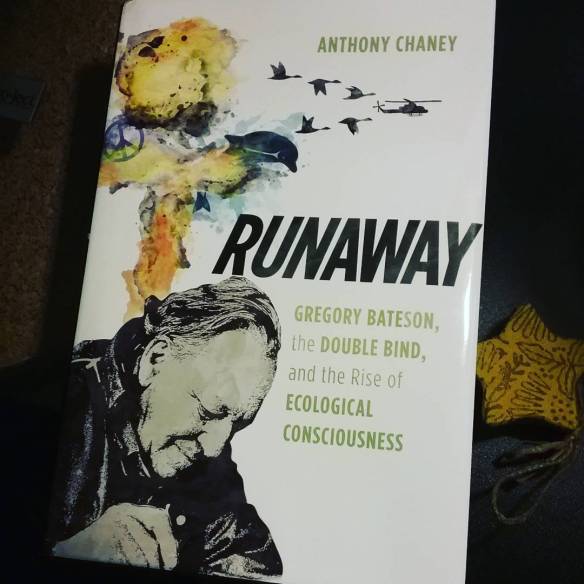

But air isn’t supposed to hurt any of us, is it? In a 1966 letter to the radical psychiatrist R. D. Laing, Gregory Bateson remarked on how human bodies had evolved according to this supposition. Unlike whales and dolphins, whose blowholes were figured according to the premise–the truth, one might say–that air was only intermittently available, human bodies were formed according to the premise that air was healthful, abundant, and available at all times, right there in front of our faces. “Modern environments” were challenging that “built-in” truth, Bateson noted. This challenge was a cause of “disturbance” in “an epoch … more deeply disturbed than any other in the history of man.”

The social disturbances of the Sixties are well-known. Bateson’s point was to urge Laing to perceive physiological, psychological, social, and environmental disturbance as formally similar phenomena. At the very least, he hoped that a kind of humility might arise from this perception—humility as to human options for dealing with disturbance. His position was that the default option was the source of a good deal of the disturbance. The default option was the drive for mastery, the epistemology of control.

“Control kills, connection heals, come home or die.” This is the written message left by the militant environmentalists in Richard Powers’ 2019 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Overstory, whenever they stage an action. The militancy isn’t Batesonian. The written message is.

Oh, where am I going with this? There’s a thread here I’m unable to grasp between my fingers. Past truths are no longer applicable, yet we still have emotional stakes in them, and in some cases, those stakes are built-in. The species of denial are manifold and respect no particular politics. They trap us into repetitive behaviors that only speed us toward the next “accident.” I began with the idea of environmental fear being under-explored, under-theorized. Bateson’s thought offers ways to think about living systems when trust deteriorates and people are afraid.

A version of this essay also appears in The Society for US Intellectual History Blog.

I suppose if one only stuck a toe into the literature of climate change, into its factual evidence, its numbers, into its long-form meditations and its day-to-day reportage, one might still be able to manage some deflection. One might still be able to push what it has to say into a corner to be visited only now and then. Put in a half of foot, however, and compartmentalization becomes almost impossible. We face a moral crisis of shattering proportions.

I suppose if one only stuck a toe into the literature of climate change, into its factual evidence, its numbers, into its long-form meditations and its day-to-day reportage, one might still be able to manage some deflection. One might still be able to push what it has to say into a corner to be visited only now and then. Put in a half of foot, however, and compartmentalization becomes almost impossible. We face a moral crisis of shattering proportions.

Not all had moved on. The mine closed in 1975, and Bisbee has survived as a small, remote high desert town. The historic district seems to have resurrected itself as an artist colony and bohemian enclave, with make-do homes up the mountain side, vintage hotels, funky shops, galleries, and sites of tourism. It’s no ghost town, but it does seem to have a fascination with the ghosts of its past. Some of these ghosts may be the disappeared, the 1200 striking miners of 1917—mostly Mexican and Eastern European–who were gathered at gunpoint, packed into cattle cars, hauled off into the desert, and abandoned. Last year’s film,

Not all had moved on. The mine closed in 1975, and Bisbee has survived as a small, remote high desert town. The historic district seems to have resurrected itself as an artist colony and bohemian enclave, with make-do homes up the mountain side, vintage hotels, funky shops, galleries, and sites of tourism. It’s no ghost town, but it does seem to have a fascination with the ghosts of its past. Some of these ghosts may be the disappeared, the 1200 striking miners of 1917—mostly Mexican and Eastern European–who were gathered at gunpoint, packed into cattle cars, hauled off into the desert, and abandoned. Last year’s film,

One essay I returned to more than once was “The Yogi and the Commissar” from 1942. It’s a good example of Koestler’s ability to capture concepts in figurative language. He begins by imagining a device able to break down the spectrum of “all possible human attitudes to life” into bands of light—a “sociological spectroscope,” he calls it. At one extreme end is the infra-red, represented in Koestler’s scheme by the Commissar. The Commissar is the ideologue, willing to take bold action, including “violence, ruse, treachery, and poison,” to achieve the goals his doctrine prescribes. Representing the opposite ultra-violet end of the spectrum is the Yogi. The Yogi’s highest value is his spiritual attachment to “an invisible navel cord” through which he is nourished by “the all-one.” The Yogi “believes that nothing can be improved by exterior organization and everything by the individual effort from within.”

One essay I returned to more than once was “The Yogi and the Commissar” from 1942. It’s a good example of Koestler’s ability to capture concepts in figurative language. He begins by imagining a device able to break down the spectrum of “all possible human attitudes to life” into bands of light—a “sociological spectroscope,” he calls it. At one extreme end is the infra-red, represented in Koestler’s scheme by the Commissar. The Commissar is the ideologue, willing to take bold action, including “violence, ruse, treachery, and poison,” to achieve the goals his doctrine prescribes. Representing the opposite ultra-violet end of the spectrum is the Yogi. The Yogi’s highest value is his spiritual attachment to “an invisible navel cord” through which he is nourished by “the all-one.” The Yogi “believes that nothing can be improved by exterior organization and everything by the individual effort from within.” The above impressions, as well as the quotes, are drawn from my reading of Michael Scammell’s 2009 biography. Scammell tells a good story, too. As for the rape charge, he doesn’t simply accept it at face value. He tries to place it in context; he airs a number of considerations. For instance: Koestler’s accuser did not speak immediately about the assault but waited for many decades to pass. She “seemed to have responded by pushing the incident to the back of her mind and accommodating herself to it.” Perhaps what Koestler did wouldn’t have been called rape then, Scammell suggests, but has only been described that way more recently. Koestler made no mention of the incident in his diary, though his diary was the place he regularly listed conquests. On the other hand, Koestler was drinking a good deal during this period, so it’s possible “he was so drunk he forgot all about it.” These considerations, read in light of the Kavanaugh scandal, land like punches to the gut.

The above impressions, as well as the quotes, are drawn from my reading of Michael Scammell’s 2009 biography. Scammell tells a good story, too. As for the rape charge, he doesn’t simply accept it at face value. He tries to place it in context; he airs a number of considerations. For instance: Koestler’s accuser did not speak immediately about the assault but waited for many decades to pass. She “seemed to have responded by pushing the incident to the back of her mind and accommodating herself to it.” Perhaps what Koestler did wouldn’t have been called rape then, Scammell suggests, but has only been described that way more recently. Koestler made no mention of the incident in his diary, though his diary was the place he regularly listed conquests. On the other hand, Koestler was drinking a good deal during this period, so it’s possible “he was so drunk he forgot all about it.” These considerations, read in light of the Kavanaugh scandal, land like punches to the gut. A passage comes in The Ghost in the Machine where Koestler raises “the moral dilemma of judging others.” He has developed an argument in which “the self-assertive, hunger-rage-fear-rape” emotions constrict “freedom of choice.” The loss of freedom in Commissar-like behaviors involve “the subjective feeling of acting under a compulsion.” “How am I to know,” Koestler asks, “whether or to what extent [a person’s] responsibility was diminished when he acted as he did, and whether he could ‘help it’?”

A passage comes in The Ghost in the Machine where Koestler raises “the moral dilemma of judging others.” He has developed an argument in which “the self-assertive, hunger-rage-fear-rape” emotions constrict “freedom of choice.” The loss of freedom in Commissar-like behaviors involve “the subjective feeling of acting under a compulsion.” “How am I to know,” Koestler asks, “whether or to what extent [a person’s] responsibility was diminished when he acted as he did, and whether he could ‘help it’?” By 1968 John Wayne was as politically polarizing a figure as he would probably ever be. In June of that year, he released his Vietnam movie, The Green Berets. He was a vocal supporter of the war, and the film had been made with the full cooperation of the Department of Defense. It presented the US mission in Vietnam as a stand for freedom and justice and blamed America’s difficulties there on a sapping of nerve perpetrated by an unpatriotic press corps. That message might have played less divisively a year earlier, before the Tet Offensive, before Lyndon Johnson’s announcement he would not run again. Screenings drew antiwar protests; reviewers pilloried the film. “The Green Berets became the focus of a divided America,” writes J. Hoberman in The Dream Life: Movies, Media, and the Mythology of the Sixties. “LBJ’s abdication left Wayne the lone authority figure standing.”

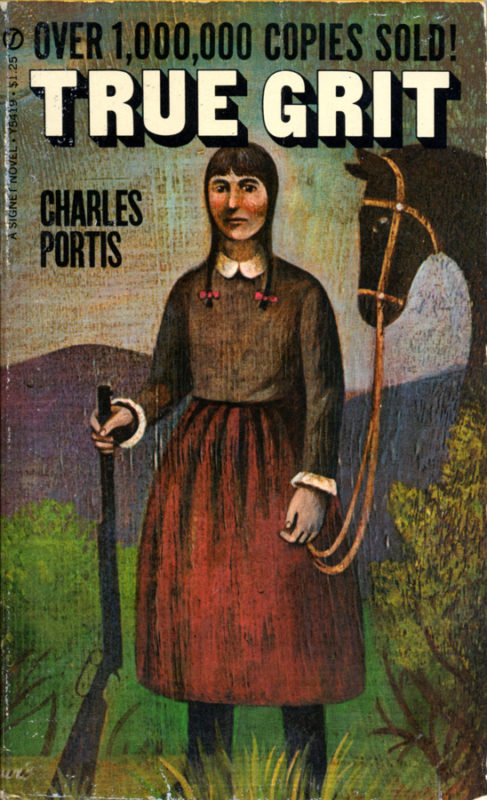

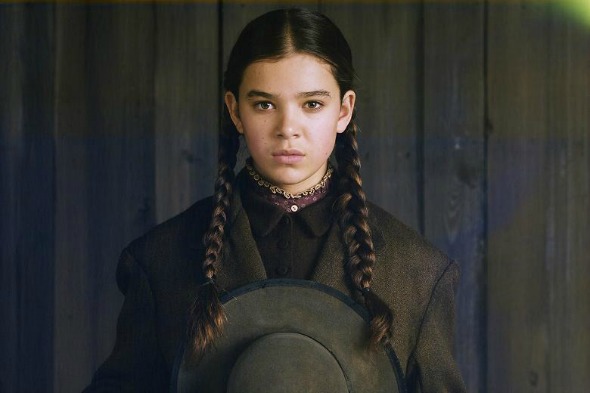

By 1968 John Wayne was as politically polarizing a figure as he would probably ever be. In June of that year, he released his Vietnam movie, The Green Berets. He was a vocal supporter of the war, and the film had been made with the full cooperation of the Department of Defense. It presented the US mission in Vietnam as a stand for freedom and justice and blamed America’s difficulties there on a sapping of nerve perpetrated by an unpatriotic press corps. That message might have played less divisively a year earlier, before the Tet Offensive, before Lyndon Johnson’s announcement he would not run again. Screenings drew antiwar protests; reviewers pilloried the film. “The Green Berets became the focus of a divided America,” writes J. Hoberman in The Dream Life: Movies, Media, and the Mythology of the Sixties. “LBJ’s abdication left Wayne the lone authority figure standing.” “I was just fourteen years old,” goes the novel’s second sentence, “when a coward going by the name of Tom Chaney shot my father down in the street in Fort Smith, Arkansas and robbed him of his life and his horse and $150 in cash money plus two California gold pieces that he carried in his trouser band.” The year is never named, but a history buff with basic math skills can figure it out—1878. Fifty years have passed since the murder, Hoover has been elected president, and a fully grown Mattie is looking back on how, at fourteen, she hired a U.S. marshal (Rooster) to track the killer into Indian territory, to catch him and exact her revenge. Her supreme confidence in the righteousness of her cause burns even brighter than does Wayne’s and his cohort for the cause in Vietnam. Mattie’s mission, too, is one of justice in the territory, as it were.

“I was just fourteen years old,” goes the novel’s second sentence, “when a coward going by the name of Tom Chaney shot my father down in the street in Fort Smith, Arkansas and robbed him of his life and his horse and $150 in cash money plus two California gold pieces that he carried in his trouser band.” The year is never named, but a history buff with basic math skills can figure it out—1878. Fifty years have passed since the murder, Hoover has been elected president, and a fully grown Mattie is looking back on how, at fourteen, she hired a U.S. marshal (Rooster) to track the killer into Indian territory, to catch him and exact her revenge. Her supreme confidence in the righteousness of her cause burns even brighter than does Wayne’s and his cohort for the cause in Vietnam. Mattie’s mission, too, is one of justice in the territory, as it were.

We were walking, my wife and I, from our parking space to the door of the Beto O’Rourke campaign office in south Dallas on the evening of its official opening celebration. Beto, running to unseat Ted Cruz in the US Senate, was scheduled to appear. Even before we got to the door, we could see a crowd of people around it and more like us converging from their own parking spaces. Coming up alongside us was Daniel, who I recognized from numerous other political events.

We were walking, my wife and I, from our parking space to the door of the Beto O’Rourke campaign office in south Dallas on the evening of its official opening celebration. Beto, running to unseat Ted Cruz in the US Senate, was scheduled to appear. Even before we got to the door, we could see a crowd of people around it and more like us converging from their own parking spaces. Coming up alongside us was Daniel, who I recognized from numerous other political events. Lawrence Wright’s book, God Save Texas, came out last spring, and I read it not long after with great pleasure. Wright is a staff writer for The New Yorker. He won a Pulitzer for his book on 9-11, The Looming Tower. A baby boomer, Wright grew up in Dallas and has lived in Austin since 1980. In this latest book, he covers all the important aspects of his home state– its cities, its regions, its history and music– but his main topic is politics. Texas politics have always had a “burlesque side,” Wright acknowledges, a “recurrent crop of crackpots and ideologues,” and now it’s as bad as it’s ever been. The problem is that the state’s size renders it especially influential. “Texas has nurtured an immature political culture that has done terrible damage to the state and to the nation,” Wright believes.

Lawrence Wright’s book, God Save Texas, came out last spring, and I read it not long after with great pleasure. Wright is a staff writer for The New Yorker. He won a Pulitzer for his book on 9-11, The Looming Tower. A baby boomer, Wright grew up in Dallas and has lived in Austin since 1980. In this latest book, he covers all the important aspects of his home state– its cities, its regions, its history and music– but his main topic is politics. Texas politics have always had a “burlesque side,” Wright acknowledges, a “recurrent crop of crackpots and ideologues,” and now it’s as bad as it’s ever been. The problem is that the state’s size renders it especially influential. “Texas has nurtured an immature political culture that has done terrible damage to the state and to the nation,” Wright believes. What was Beto like? What did he do and say? I won’t belabor this much further. You can get a look at him and hear him speak in any number of settings—the video links on Youtube are legion. His answer to a town hall question about kneeling during the anthem has recently gone viral, for whatever that’s worth. This was my third time to see him live, however. The first time was on a corner at a march in support of immigrants, before many knew who he was. The second time was well into the race, in the Texas Theater, the old movie house where they arrested Oswald, and there was a line down the block to get in. So how did this third time compare?

What was Beto like? What did he do and say? I won’t belabor this much further. You can get a look at him and hear him speak in any number of settings—the video links on Youtube are legion. His answer to a town hall question about kneeling during the anthem has recently gone viral, for whatever that’s worth. This was my third time to see him live, however. The first time was on a corner at a march in support of immigrants, before many knew who he was. The second time was well into the race, in the Texas Theater, the old movie house where they arrested Oswald, and there was a line down the block to get in. So how did this third time compare?