The following is my response to a roundtable published at the Society for US Intellectual History Blog. Links to the essays in the roundtable can be found here.

Not long before going into the room to defend my dissertation, I was advised by a mentor–and I’m paraphrasing–“This may be the only time your scholarship will ever receive such close attention. Enjoy it.”

I’m just going to give anyone who’s ever defended a dissertation a moment to reflect on these remarks, to savor their layers of meaning, and maybe to chuckle at them a little ruefully, as I did in that small part of my brain where, at that point in my academic career, I still had room left to entertain a complex truth.

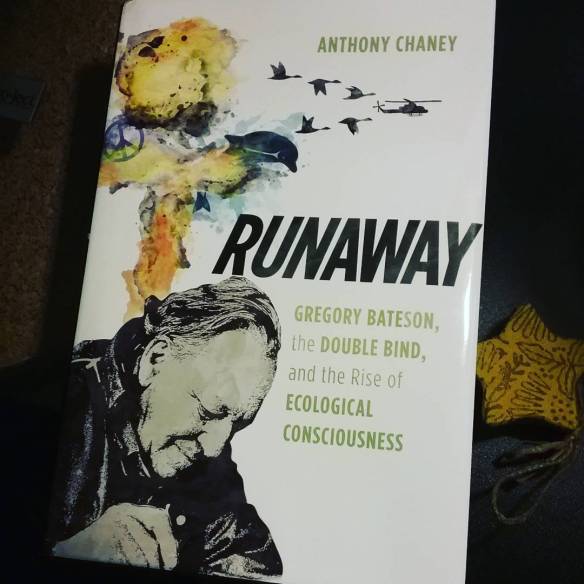

Because, I want to say, this was indeed honest advice, full of plainspoken wisdom, and yet the prediction it contained turned out not to be accurate, after all. Here at the S-USIH Blog, three scholars have weighed in on my book, Runaway: Gregory Bateson, the Double Bind, and the Rise of Ecological Consciousness. I share the anecdote above as way to tell these three, Colin Campbell, Michael Kramer, and Lilian Calles Barger, how grateful I am for this roundtable and for their engagement with the book–and how I don’t take it for granted even a tiny bit.

Each of these reviewers offers summary statements so concise and so accurate as to make an author teary-eyed. More productive, if less wholly pleasing, is the feedback these readers bring that pertains to what was left out of the book, what I might have explored further, or more critically, what I raised as a central issue but did not make fully clear. These are the matters I’ll focus on here.

First, however, a few brief summary statements of my own may be necessary. Michael J. Kramer does the book a service by clarifying its central concerns: the double bind concept, the related concept of systemic runaway, and the moral implications that a systemic orientation raises, which Bateson would capture in the phrase, “the riddle of the Sphinx.” These concerns, in turn, provided a ten-year narrative arc the book loosely follows: the construction of double bind theory in 1956 through its application to the discourse of ecocatastrophe at the Congress on the Dialectics of Liberation in the summer of 1967–and in what may be the first discussion of global warming before a lay audience.

That audience, of course, is vital to any contextual understanding of these concepts and events. As a scholar who has done so much work in the cultural history of the 1960s, Kramer knows that audience well. It was one raised to oppose, as if by instinct, totalitarianism in all its forms and to exalt individual free expression. How to square this with ecological holism? In raising the whole above the parts, didn’t one run the risk of inscribing morality into nature, and succumbing to, as one of the historians Bateson corresponded with put it, “the siren to be feared”? Fascism, with its naturalization of the body politic, had only recently been defeated, perhaps only temporarily. Kramer puts his finger on a concern that would become more salient in the seventies, the eighties, and beyond: Weren’t those persuaded by systemic thinking now vulnerable to neoliberalism and its trust in the free market as a system and, as Kramer puts it, “ultimate balance by the invisible hands”? If I could continue the path this book opens, and follow Bateson’s thought into the next decade, this would be one of my guiding questions.

Still, I think a response to the question is present in the book. Yes, according to a systems view, the free market is a system over which no individual or group has control. Like all systems, it processes information running in circuits, reinforcing basic premises, conserving ‘sacred’ truths. If those truths include the belief that human beings are creatures whose survival necessitates the maximization of self-interest, an economy dependent upon endless capital accumulation and reproduction is the sort one would expect to get. As early as 1958, Bateson described a culture in a double bind. “From its own point of view, the culture faces either external extermination or internal disruption, and the dilemma is so constructed as to be a dilemma of self-preservation in the most literal sense” (254). We might apply this description to our present-day economic system. To preserve a self dedicated to full individuation means extinction at the cultural level. Preserving the culture means disrupting if not extinguishing the fully individuated self.

Colin Campbell might put the situation a bit differently. It was especially challenging for me to think through his request for greater coherence as to the “battle of ideas” at the core of the book. Campbell identifies this battle as a battle between atomistic and holistic epistemologies as illustrated by Mary Catherine Bateson’s left (atomistic) and right (holistic) columns, which she produced in the thick of the conference her father led in Austria of the summer of 1968. This is an accurate breakdown, as far as it goes. I wasn’t thinking, however, quite so schematically. I didn’t draw so close an equivalence between Batesonian epistemology, as I summarize it in the introduction of the book, and Mary Catherine Bateson’s right-hand column. Nor do I see as automatic an equivalence between the right-hand column and the position of the “mindblowers” at the 1967 Congress on the Dialectics of Liberation in their contest with the politicos on the nature of revolution.

In short, I may be working a little closer in than Campbell would prefer. As I see it, this wasn’t a single battle of ideas; it was several battles. They were related, to be sure, but distinguished from each other by an ever-changing historical context. I do think Bateson believed his more process- and relations-oriented epistemology to be superior to and should replace an obsolete, “thingish” epistemology (3, 78), simply because it provided a more accurate view of nature and of ourselves. But because I didn’t draw the initial equivalences that Campbell draws, that isn’t the same thing as saying that Bateson believed that Mary Catherine’s right column ought to “eat” her left one.

Yet Campbell’s request for more coherence on this central question is a valid criticism. Does Bateson’s thought transcend or merge the left column’s straightforwardness and the right column’s complexity, and if so, how? This is the million-dollar question, and Campbell’s elucidation of the simplicity/complexity dichotomy was excellent in posing it clearly. I benefited, too, from his detailing, through examples, of the “intra- to each side.” His application of Virginia Satir’s quadrant sharpened the theoretical focus even further.

I would only ask whether this analysis takes us any closer to the merger of left and right sides that we desire? I tend to think not. I resist a rhetorical closure on the question in favor of a contextually rich historical depiction. When we concentrate on the ideas alone and lose the messy story, the picture becomes less accurate, if less satisfying in terms of a conclusion. The dilemma captured by the double bind concept is the merger, it seems to me—or was, anyway, in the summer of 1967. Thus, as Campbell recognizes, the question remains open, as I think it must: How do we stand meta to the dichotomy? I’m informed by Campbell’s bio that he’s working on a couple of studies of Bateson’s thought that I expect will offer a more decisive interpretation. I’m looking forward to reading them.

The merger that Bateson sought to capture epistemologically ran parallel to other similar projects across many registers and bodies of knowledge during the period in question. Sometimes the merger was called a “third way” (239, 249) or, as Lilian Calles Barger puts it in her reflection, “a higher synthesis.” Barger’s book, The World Come of Age, traces this project among liberation theologians in the 1960s and 70s. It isn’t surprising, then, that Barger would call attention to “the mystical Bateson,” another aspect of Bateson’s thought that is raised in my book but not as thoroughly examined as it might have been.

Certainly, the tensions between spirituality and secularity were never far away from the story I tried to tell. Throughout the modern age, but after Darwin especially, liberal theologians found ways to accommodate religion to the rising authority of science: this was the modernist model. What was essentially postmodernist in Bateson’s thought, as I see it, was its reversal of this trend. He argued for an accommodation by science to the religious impulse, broadly understood. As a trained anthropologist, for whom the line between nature and culture was permeable, he read religious behavior as part of humankind’s natural history. As a scientist for whom no area of investigation was separable from its contexts, he concluded that all human investigation of the surrounding world was reflexively an investigation of the human. Here the religious and scientific impulses were on a par.

Much of Bateson’s lay audience grasped this intuitively. Bateson would reject the status of “guru” even though many wished to see him that way. This rejection, another of Bateson’s great refusals, was complicated by the fact that New Age-ish institutions provided aid to him during the trials of his final years. Also, starting in the 1970s, Bateson’s thought was often lumped with the thinking of a less-rigorous body of enthusiasm. The marginalization of much of what I would call postmodern science is a story that bears investigation. Again, if I had the chance to continue my contextualization of Bateson’s thought after his emergence as a public intellectual in 1967 and through the remaining years of his life, this story would be included.

In responding to issues raised by my reviewers that were not fully explored or resolved in the book, I’ve pointed in each case to the following period, after the 1967-68 turning point, to the other side of my narrative arc. That’s a little embarrassing. If I’ve given short shrift to all I did include, my reviewers mentioned a good bit of it, and again I want to thank them for that. But I also want to make one last point. I alluded above to working “close in.” In writing this book, I tried to stand meta to an analytical/aesthetic dichotomy, too. Part of that meant drawing boundaries. Some stories just can’t be told in one volume, not the way they ought to be, anyway.

A version of this essay appears at the S-USIH Blog.

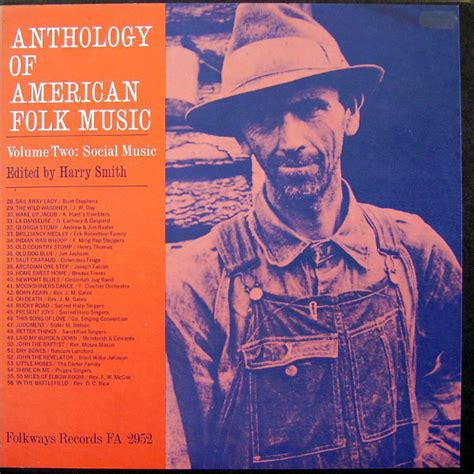

song. What ballads shared, Smith suggests in his notes, is their “narrative unity.” This posits some distance between the making of the lyrics and the singing of them. A story not only occurs in a distant time, it must also be prepared, its beginning, middle, and end worked out, prior to its performance. Songs may be no less prepared, but the impression they are meant to convey is one of immediacy. This song is “taking place as you listen.” The singer’s individuality and the immediacy of the performance are the point. The singer is the center of the song, the chief character who feels the song as it’s performed, and who the listeners are urged to identify with so to experience their own individuality.

song. What ballads shared, Smith suggests in his notes, is their “narrative unity.” This posits some distance between the making of the lyrics and the singing of them. A story not only occurs in a distant time, it must also be prepared, its beginning, middle, and end worked out, prior to its performance. Songs may be no less prepared, but the impression they are meant to convey is one of immediacy. This song is “taking place as you listen.” The singer’s individuality and the immediacy of the performance are the point. The singer is the center of the song, the chief character who feels the song as it’s performed, and who the listeners are urged to identify with so to experience their own individuality. Reading in the literature of degrowth, I find much to be charmed by, not least the following quote from

Reading in the literature of degrowth, I find much to be charmed by, not least the following quote from  realities: 1) the conditions of our environment are rapidly deteriorating, and 2) the ‘grow or die’ imperative, which practically all economists and politicians accept as the solution to our problems, is in fact the primary cause. Degrowth is also an investigation and a provisional encouragement of those local and regional experiments, going on in various parts of the world, in exiting the growth economy. The degrowth perspective is organized around the values of sufficiency, simplicity, conviviality, and sharing–not the value of individual material accumulation.

realities: 1) the conditions of our environment are rapidly deteriorating, and 2) the ‘grow or die’ imperative, which practically all economists and politicians accept as the solution to our problems, is in fact the primary cause. Degrowth is also an investigation and a provisional encouragement of those local and regional experiments, going on in various parts of the world, in exiting the growth economy. The degrowth perspective is organized around the values of sufficiency, simplicity, conviviality, and sharing–not the value of individual material accumulation. growth as an aspect of something more general. Humankind’s “insatiable desire for growth” is “not merely for economic growth but for growth in experience, in pleasure, in knowledge, in sensibility.” That defining insatiability drives us ever upward and onward. Granted unlimited powers by Mephistopheles, Goethe’s Faust quickly burns through the thrills of hedonism, destroying the lives of those he loves along the way. Faust then commits those powers to bettering society with a massive Robert Moses-like makeover. He sets out to become the kind of hero Ayn Rand would later champion in a lower literary register: a builder of great projects of infrastructure. When human insatiability takes economic expression, growth for growth’s sake is the inevitable consequence. Now it isn’t just a few loved ones who are destroyed. Now whole societies and ecosystems are bulldozed and shoveled over, mobilized, reintegrated, and then bulldozed and shoveled over again.

growth as an aspect of something more general. Humankind’s “insatiable desire for growth” is “not merely for economic growth but for growth in experience, in pleasure, in knowledge, in sensibility.” That defining insatiability drives us ever upward and onward. Granted unlimited powers by Mephistopheles, Goethe’s Faust quickly burns through the thrills of hedonism, destroying the lives of those he loves along the way. Faust then commits those powers to bettering society with a massive Robert Moses-like makeover. He sets out to become the kind of hero Ayn Rand would later champion in a lower literary register: a builder of great projects of infrastructure. When human insatiability takes economic expression, growth for growth’s sake is the inevitable consequence. Now it isn’t just a few loved ones who are destroyed. Now whole societies and ecosystems are bulldozed and shoveled over, mobilized, reintegrated, and then bulldozed and shoveled over again. instead reach for something more transparently convivial. Berman believes “the wounds of modernity can only be healed by a fuller and deeper modernism.” “Modern men and women must learn to yearn for change,” he writes, but his construction doesn’t allow them any objective for change except to better surf the same wave of endless development. Is there no exit from this central, self-reinforcing dynamic? “Sure, there is!” the degrowthers say.

instead reach for something more transparently convivial. Berman believes “the wounds of modernity can only be healed by a fuller and deeper modernism.” “Modern men and women must learn to yearn for change,” he writes, but his construction doesn’t allow them any objective for change except to better surf the same wave of endless development. Is there no exit from this central, self-reinforcing dynamic? “Sure, there is!” the degrowthers say.

rule at the box office, it seems. Ironman dons his suit. Bullets can’t penetrate that garment–that garment of technological genius that is going to save us from all threats. We know the cinematic ritual. The dance ends the same way every time. The fate of the world has come down to a single bout between Ironman and his adversary. Throughout this protracted battle—all the getting knocked down and the getting back up again–all manner of infrastructure is laid to waste. Roads and bridges, buildings, innumerable cars. This is the most tedious and least dispensable part of the ritual. Here the contradictions at play achieve an almost seamless merger.

rule at the box office, it seems. Ironman dons his suit. Bullets can’t penetrate that garment–that garment of technological genius that is going to save us from all threats. We know the cinematic ritual. The dance ends the same way every time. The fate of the world has come down to a single bout between Ironman and his adversary. Throughout this protracted battle—all the getting knocked down and the getting back up again–all manner of infrastructure is laid to waste. Roads and bridges, buildings, innumerable cars. This is the most tedious and least dispensable part of the ritual. Here the contradictions at play achieve an almost seamless merger.

interruption of social flows, the detachment of consciousness from impulse” as a “radical practice,” I begin to feel somewhat cheered. “We must inculcate ruminative frequencies in the human animal,” Scranton writes, “by teaching slowness, attention to detail, argumentative rigor, careful reading, and meditative reflection.” These are different ways to describe what he calls “philosophical humanism,” and which I understand as instruction and scholarly practice in the humanities. It’s a relief to be informed that what one must do to combat climate change is what one most enjoys doing and would likely be doing, anyway.

interruption of social flows, the detachment of consciousness from impulse” as a “radical practice,” I begin to feel somewhat cheered. “We must inculcate ruminative frequencies in the human animal,” Scranton writes, “by teaching slowness, attention to detail, argumentative rigor, careful reading, and meditative reflection.” These are different ways to describe what he calls “philosophical humanism,” and which I understand as instruction and scholarly practice in the humanities. It’s a relief to be informed that what one must do to combat climate change is what one most enjoys doing and would likely be doing, anyway. In one sequence from

In one sequence from  Played by Steve McQueen, Thomas Crown is a young Boston Brahmin, rich and smart, who runs an investment company specializing in currencies. He’s one of those “Masters of the Universe” that would be held up for scorn by Tom Wolfe and Oliver Stone in the 1980s, but in this film, he’s the ideal. The film opens with Crown organizing and pulling off a complicated bank heist. This portion of the film pioneers a highly stylized multiple-screen technique that allows the audience to follow Crown as he sits at his desk and executes his many-faceted plan. He employs operatives in gray suits and dark glasses, strangers both to him and to each other. It’s the perfect crime, and Crown its godlike master, omniscient yet unknown to all, pulling the strings from his high-rise perch. The remainder of the film celebrates that mastery and asks whether it will go unchecked. Faye Dunaway plays the brilliant insurance investigator hot on his trail, a happy warrior with a liking for haute couture. T

Played by Steve McQueen, Thomas Crown is a young Boston Brahmin, rich and smart, who runs an investment company specializing in currencies. He’s one of those “Masters of the Universe” that would be held up for scorn by Tom Wolfe and Oliver Stone in the 1980s, but in this film, he’s the ideal. The film opens with Crown organizing and pulling off a complicated bank heist. This portion of the film pioneers a highly stylized multiple-screen technique that allows the audience to follow Crown as he sits at his desk and executes his many-faceted plan. He employs operatives in gray suits and dark glasses, strangers both to him and to each other. It’s the perfect crime, and Crown its godlike master, omniscient yet unknown to all, pulling the strings from his high-rise perch. The remainder of the film celebrates that mastery and asks whether it will go unchecked. Faye Dunaway plays the brilliant insurance investigator hot on his trail, a happy warrior with a liking for haute couture. T he two are superior persons: equally beautiful and equally amoral, in need of no one, and therefore, perfect for each other.

he two are superior persons: equally beautiful and equally amoral, in need of no one, and therefore, perfect for each other. Crown will be held responsible for his actions. For those who haven’t seen the movie, I won’t spoil the end, except to say that the modern dream of mastery goes unchallenged here. There’s nary a whiff of the tragic end to that dream that the ecological imagination will struggle to apprehend.

Crown will be held responsible for his actions. For those who haven’t seen the movie, I won’t spoil the end, except to say that the modern dream of mastery goes unchallenged here. There’s nary a whiff of the tragic end to that dream that the ecological imagination will struggle to apprehend.