“Ford v. Ferrari,” now playing in cinemas, is about a maverick team of car designers and drivers who have been commanded by the Ford Corporation to build a car that will win at Le Mans. In one scene, corporate head Henry Ford II is unexpectedly taken for his first ride in the GT40, the car his crew is piloting. The car takes off, and Ford is rocketed up and down an airport runway, his face frozen in terror. This is about the time a newbie soils himself, a seasoned observer remarks.

When the car finally screams to a halt, Ford bursts into a fit of weeping. At first he seems unmanned—‘crying like a little girl,’ to quote a familiar gibe. But then we learn the real reason for his tears. If only granddad could see this, he says. The implication is that jetting a human body 200 miles per hour over a patch of cement was what his legendary namesake was really after all along. To push a limit, to break a record, to go faster. The sacralization of speed (and masculinity) is a move the film makes over and over. Whether automobile or airplane or rocket ship, the petroleum-fueled combustion engine is the machine men have made to surpass limitation.

What’s the old riddle about Mount Everest? “Because it’s there.” For as long as I can remember, this ‘breaking of a limit for its own sake’ has been lifted up and celebrated as the quintessential mark of human distinction

How have we come to think about limits this way? How has the idea of limits shaped our economics, our politics, and our relationship with the living world around us? These are precisely the questions Giorgos Kallis asks in Limits, his new book from Stanford Briefs.

A prominent advocate for degrowth, Kallis is a prolific writer of articles and books that deliver careful research and argument in no-nonsense persuasive prose. (One of his sidelines are essays on how to be a productive academic.) Born in Athens, educated transnationally, Kallis is an environmental scientist working in the field of political ecology and a professor at the Autonomous University in Barcelona. Limits, however, is a straight-ahead history of ideas. It’s based on a reading of a classic text, Thomas Robert Malthus’s 1798 essay on population and food supply. The subtitle of Kallis’s short book is Why Malthus was Wrong and Why Environmentalists Should Care.

The argument is a little difficult to put succinctly because it runs so counter to the way Malthus has been commonly understood. Malthus, the prophet of scarcity, said that human population would always outrun the amount of available food. Malthusian pessimism signifies a kind of regressive blindness to the human capacity to surpass limits, to innovate, and to discover new sources of fuel, both for our bodies and for our machines. This popular understanding of Malthus comes from a mis- or half-reading, Kallis finds.

Kallis stresses the political motivation behind the essay. In 1798, Malthus was writing expressly to refute those who were challenging the new capitalist order and calling for redistribution. Because we’d never have enough to feed the poor out of current stock, he countered, continuous exertion was necessary to stay ahead of the geometric ratio. So, yes, Malthus did raise the prospect of a limit to human reproduction, but it was only to remove the prospect of a limit to economic growth. Malthus’s genius was “that he managed to make scarcity compatible with growth, limits with no limits,” Kallis writes. His essay was “the first rejection of redistribution and welfare in the name of growth of free markets” (29, 21).

So Malthus was wrong, Kallis argues, but not for the reasons popularly understood. He was wrong, first, to assume that the human species was incapable of regulating its own reproduction. Second, Malthus was wrong to assume that the Earth was capable of sustaining the ever-increasing demand on its resources that was necessary. This should matter to environmentalists because environmentalists have largely accepted Malthus’s model of inevitable scarcity. They have taken upon themselves the mantle of Malthusian pessimism. When they argue that we are confronting nature’s limits, they re-inscribe Malthus’s growth calculus and reduce their own case “to a sterile scientific dispute … of how growth can be sustained and for how long.” Environmental policies become bleak schemes to stave off, for as long as possible, the day of reckoning (48).

But thresholds need not ever be passed, Kallis claims. Limits don’t exist out there in nature. They exist in our own intentions, how we define the good life, and most of all, in our politics. Those concerned about economic, social, and environmental justice shouldn’t be trying to figure out how to make growth more efficient and sustainable. Rather, they should abandon growth as a goal altogether and work to institute a “non-fatalistic politics of [self-imposed] limits” (62). Malthus taught that sharing will do no good because there would never be enough for everyone. Kallis argues that we will only have enough when we limit ourselves to our fair share. The problem isn’t natural. It’s social and political.

I’m one who’d only dipped into Malthus’s essay and had received its common meaning without question. Kallis’s reading isn’t an in-depth engagement with the original text—the book is less than 150 pages, after all—and it likely fits his degrowth agenda a bit too cleanly. But a reconsideration of Malthus, like recent ones of Adam Smith, is a welcome part of the assault, across many fronts, on the neoliberal order.

In the second half of Limits, Kallis touches on his own biography, which is something I’d not seen in his writing before. He was close to his mother, an Athens activist, and her death, when he was a young scholar, hit him hard. Among her possessions, he found the book she’d long kept by her bedside. Its author was the Greek political theorist Cornelius Castoriadis. His mother’s favorite theorist would have a great influence on his own intellectual journey. We see something of this in the second half of the book, a discussion of the relationship between self-restraint and freedom, which comes partly from Castoriadis and his understanding of the culture of ancient Greece.

There doesn’t seem to be a lot of Castoriadis readily available to the American reader. I found a copy of A Society Adrift, a compilation of late interviews and writings, which Kallis cites a good deal in Limits. I felt some due diligence was required in regard to Castoriadis’s concept of “the social imaginary.” It’s a term I’ve used a lot in the last couple of years, having picked it up from my reading in the environmental humanities, without really grasping its provenance. The term seems a lot like the terms worldview, or mindset, or paradigm, or episteme, which is to say, it aids in articulating the relationship between our immaterial ideas, our immaterial descriptions of those ideas, and the material world we come to live in as a result.

Castorious develops his explanation of the social imaginary with dense intricacy; this concept and his thinking in general shows the influence of systems theory. The systems theorist Dana Meadows confronts the matter and sums it up quite simply: “A society that talks incessantly about ‘productivity’ but that hardly understands, much less uses, the word ‘resilience’ is going to become productive and not resilient. A society that doesn’t understand or use the term ‘carrying capacity’ will exceed its carrying capacity” (174). Kallis would probably see some re-inscription of Malthus in Meadows’ thought, but they share a foundation in the importance of frames, rules, and goals in contemplating how to work toward change in a destructive system spinning out of control.

Anyway, here’s a tip: don’t go see Ford v. Ferrari if you’ve been reading Meadows, Kallis, or Cornelius Castoriadis. Or at least, if you do, don’t expect to enjoy it. As I watched, Castoriadis’s various descriptions of the “capitalist imaginary” were fresh in my mind. History had seen conquerors who thirsted for power before, Castoriadis explains. “But with capitalism, for the first time, this tendency toward the unlimited extension of might, or of mastery, encountered the appropriate, adequate instruments: ‘rational’ instruments'” (62). Henry Ford II is buckled into one of those rational instruments. He experiences this expansion of mastery in real time, as it were.

The thing about imaginaries is that they can be challenged; they can be replaced. That’s the theory, anyway, and the basis of Kallis’s political project. He relies on what Castoriadis calls “autonomy,” the capacity to continually critique both the imaginaries that dominate our perception as well as those we put up, experimentally, as alternatives. “We can have less suffering instead of destruction,” Kallis writes, “to the extent that we can institute mechanisms that help us reflect on our wants and prudently manage those that are excessive. At the level of the individual, this is the mission of psychoanalysis; at the level of the collective, Castoriadis argued, this is the role of democracy” (93).

Today, with democracy on the ropes and growth in throughput still the barely-questioned measure of all economic success, one can’t help but ask if imagining a steady-state economics of sharing isn’t too flatly utopian. It is, I suppose, if one’s thinking is shaped by Malthus’s model of scarcity. It is if one’s politics is shaped by fear of apocalyptic collapse. And it is if one’s definition of the good life is shaped by a devotion to ever-increasing, ever-accelerating production, consumption, and speed.

A version of this essay appears at the Society for US History Blog.

WORKS CITED

Castoriadis, Cornelius, Enrique Escobar, Myrto Gondicas, and Pascal Vernay. A Society Adrift Interviews and Debates, 1974-1997. 2010.Bottom of Form

Kallis, Giorgos. Limits: Why Malthus Was Wrong and Why Environmentalists Should Care. 2019.

Meadows, Donella H., and Diana Wright. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. 2015.

Some bodies were more vulnerable than others. Mothers, pregnant women, and children were the first advised to evacuate. In abstract terms, they represented what was most in peril–a society’s ability to reproduce itself. The symbols adopted by the movement came to reflect this. Biotic nationalism was “shot through with ecologically derived images of the vulnerable bodies of mothers, babies, and fetuses” (13). Meanwhile, within conservative politics more broadly, the rights of the unborn were likewise moving to the center of concern.

Some bodies were more vulnerable than others. Mothers, pregnant women, and children were the first advised to evacuate. In abstract terms, they represented what was most in peril–a society’s ability to reproduce itself. The symbols adopted by the movement came to reflect this. Biotic nationalism was “shot through with ecologically derived images of the vulnerable bodies of mothers, babies, and fetuses” (13). Meanwhile, within conservative politics more broadly, the rights of the unborn were likewise moving to the center of concern.  At first, “Air can hurt you, too,” seems a neurotic claim. It fits the twitchy, hyper-literal persona David Byrne had established with the group’s first two records. The song is less a warning about air than it is a warning about fear. Its underlying message–its wider inference in the Byrne program–is to push past fear and to embrace life’s wonderful messiness. The theme would become more direct in subsequent records. But the song’s conceit only works if the claims made about air are perceived as paranoid, which they aren’t, by any means. Air can hurt us. Millions die from dirty air every year around the globe, most especially in the global south, where our fossil-fuel-based economics tends to shunt its externalities. Would the song make sense at all in a place where people don surgical masks to go out of doors? These considerations push the song even further away from an environmentalist reading. Or we might put it this way: “Air” functions in a space of relative privilege.

At first, “Air can hurt you, too,” seems a neurotic claim. It fits the twitchy, hyper-literal persona David Byrne had established with the group’s first two records. The song is less a warning about air than it is a warning about fear. Its underlying message–its wider inference in the Byrne program–is to push past fear and to embrace life’s wonderful messiness. The theme would become more direct in subsequent records. But the song’s conceit only works if the claims made about air are perceived as paranoid, which they aren’t, by any means. Air can hurt us. Millions die from dirty air every year around the globe, most especially in the global south, where our fossil-fuel-based economics tends to shunt its externalities. Would the song make sense at all in a place where people don surgical masks to go out of doors? These considerations push the song even further away from an environmentalist reading. Or we might put it this way: “Air” functions in a space of relative privilege. I suppose if one only stuck a toe into the literature of climate change, into its factual evidence, its numbers, into its long-form meditations and its day-to-day reportage, one might still be able to manage some deflection. One might still be able to push what it has to say into a corner to be visited only now and then. Put in a half of foot, however, and compartmentalization becomes almost impossible. We face a moral crisis of shattering proportions.

I suppose if one only stuck a toe into the literature of climate change, into its factual evidence, its numbers, into its long-form meditations and its day-to-day reportage, one might still be able to manage some deflection. One might still be able to push what it has to say into a corner to be visited only now and then. Put in a half of foot, however, and compartmentalization becomes almost impossible. We face a moral crisis of shattering proportions.

Not all had moved on. The mine closed in 1975, and Bisbee has survived as a small, remote high desert town. The historic district seems to have resurrected itself as an artist colony and bohemian enclave, with make-do homes up the mountain side, vintage hotels, funky shops, galleries, and sites of tourism. It’s no ghost town, but it does seem to have a fascination with the ghosts of its past. Some of these ghosts may be the disappeared, the 1200 striking miners of 1917—mostly Mexican and Eastern European–who were gathered at gunpoint, packed into cattle cars, hauled off into the desert, and abandoned. Last year’s film,

Not all had moved on. The mine closed in 1975, and Bisbee has survived as a small, remote high desert town. The historic district seems to have resurrected itself as an artist colony and bohemian enclave, with make-do homes up the mountain side, vintage hotels, funky shops, galleries, and sites of tourism. It’s no ghost town, but it does seem to have a fascination with the ghosts of its past. Some of these ghosts may be the disappeared, the 1200 striking miners of 1917—mostly Mexican and Eastern European–who were gathered at gunpoint, packed into cattle cars, hauled off into the desert, and abandoned. Last year’s film,

One essay I returned to more than once was “The Yogi and the Commissar” from 1942. It’s a good example of Koestler’s ability to capture concepts in figurative language. He begins by imagining a device able to break down the spectrum of “all possible human attitudes to life” into bands of light—a “sociological spectroscope,” he calls it. At one extreme end is the infra-red, represented in Koestler’s scheme by the Commissar. The Commissar is the ideologue, willing to take bold action, including “violence, ruse, treachery, and poison,” to achieve the goals his doctrine prescribes. Representing the opposite ultra-violet end of the spectrum is the Yogi. The Yogi’s highest value is his spiritual attachment to “an invisible navel cord” through which he is nourished by “the all-one.” The Yogi “believes that nothing can be improved by exterior organization and everything by the individual effort from within.”

One essay I returned to more than once was “The Yogi and the Commissar” from 1942. It’s a good example of Koestler’s ability to capture concepts in figurative language. He begins by imagining a device able to break down the spectrum of “all possible human attitudes to life” into bands of light—a “sociological spectroscope,” he calls it. At one extreme end is the infra-red, represented in Koestler’s scheme by the Commissar. The Commissar is the ideologue, willing to take bold action, including “violence, ruse, treachery, and poison,” to achieve the goals his doctrine prescribes. Representing the opposite ultra-violet end of the spectrum is the Yogi. The Yogi’s highest value is his spiritual attachment to “an invisible navel cord” through which he is nourished by “the all-one.” The Yogi “believes that nothing can be improved by exterior organization and everything by the individual effort from within.” The above impressions, as well as the quotes, are drawn from my reading of Michael Scammell’s 2009 biography. Scammell tells a good story, too. As for the rape charge, he doesn’t simply accept it at face value. He tries to place it in context; he airs a number of considerations. For instance: Koestler’s accuser did not speak immediately about the assault but waited for many decades to pass. She “seemed to have responded by pushing the incident to the back of her mind and accommodating herself to it.” Perhaps what Koestler did wouldn’t have been called rape then, Scammell suggests, but has only been described that way more recently. Koestler made no mention of the incident in his diary, though his diary was the place he regularly listed conquests. On the other hand, Koestler was drinking a good deal during this period, so it’s possible “he was so drunk he forgot all about it.” These considerations, read in light of the Kavanaugh scandal, land like punches to the gut.

The above impressions, as well as the quotes, are drawn from my reading of Michael Scammell’s 2009 biography. Scammell tells a good story, too. As for the rape charge, he doesn’t simply accept it at face value. He tries to place it in context; he airs a number of considerations. For instance: Koestler’s accuser did not speak immediately about the assault but waited for many decades to pass. She “seemed to have responded by pushing the incident to the back of her mind and accommodating herself to it.” Perhaps what Koestler did wouldn’t have been called rape then, Scammell suggests, but has only been described that way more recently. Koestler made no mention of the incident in his diary, though his diary was the place he regularly listed conquests. On the other hand, Koestler was drinking a good deal during this period, so it’s possible “he was so drunk he forgot all about it.” These considerations, read in light of the Kavanaugh scandal, land like punches to the gut. A passage comes in The Ghost in the Machine where Koestler raises “the moral dilemma of judging others.” He has developed an argument in which “the self-assertive, hunger-rage-fear-rape” emotions constrict “freedom of choice.” The loss of freedom in Commissar-like behaviors involve “the subjective feeling of acting under a compulsion.” “How am I to know,” Koestler asks, “whether or to what extent [a person’s] responsibility was diminished when he acted as he did, and whether he could ‘help it’?”

A passage comes in The Ghost in the Machine where Koestler raises “the moral dilemma of judging others.” He has developed an argument in which “the self-assertive, hunger-rage-fear-rape” emotions constrict “freedom of choice.” The loss of freedom in Commissar-like behaviors involve “the subjective feeling of acting under a compulsion.” “How am I to know,” Koestler asks, “whether or to what extent [a person’s] responsibility was diminished when he acted as he did, and whether he could ‘help it’?” By 1968 John Wayne was as politically polarizing a figure as he would probably ever be. In June of that year, he released his Vietnam movie, The Green Berets. He was a vocal supporter of the war, and the film had been made with the full cooperation of the Department of Defense. It presented the US mission in Vietnam as a stand for freedom and justice and blamed America’s difficulties there on a sapping of nerve perpetrated by an unpatriotic press corps. That message might have played less divisively a year earlier, before the Tet Offensive, before Lyndon Johnson’s announcement he would not run again. Screenings drew antiwar protests; reviewers pilloried the film. “The Green Berets became the focus of a divided America,” writes J. Hoberman in The Dream Life: Movies, Media, and the Mythology of the Sixties. “LBJ’s abdication left Wayne the lone authority figure standing.”

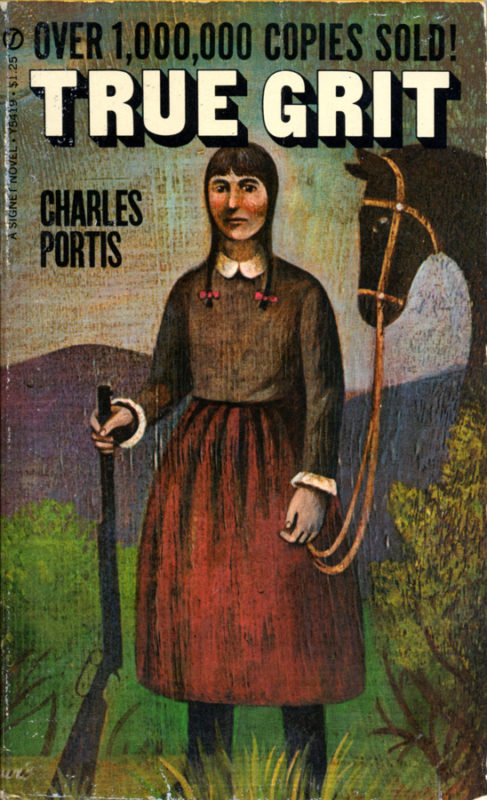

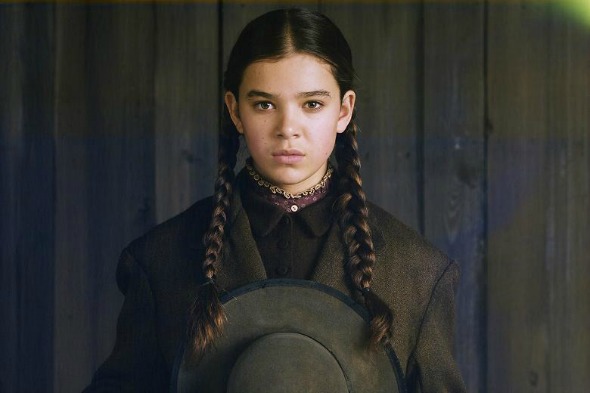

By 1968 John Wayne was as politically polarizing a figure as he would probably ever be. In June of that year, he released his Vietnam movie, The Green Berets. He was a vocal supporter of the war, and the film had been made with the full cooperation of the Department of Defense. It presented the US mission in Vietnam as a stand for freedom and justice and blamed America’s difficulties there on a sapping of nerve perpetrated by an unpatriotic press corps. That message might have played less divisively a year earlier, before the Tet Offensive, before Lyndon Johnson’s announcement he would not run again. Screenings drew antiwar protests; reviewers pilloried the film. “The Green Berets became the focus of a divided America,” writes J. Hoberman in The Dream Life: Movies, Media, and the Mythology of the Sixties. “LBJ’s abdication left Wayne the lone authority figure standing.” “I was just fourteen years old,” goes the novel’s second sentence, “when a coward going by the name of Tom Chaney shot my father down in the street in Fort Smith, Arkansas and robbed him of his life and his horse and $150 in cash money plus two California gold pieces that he carried in his trouser band.” The year is never named, but a history buff with basic math skills can figure it out—1878. Fifty years have passed since the murder, Hoover has been elected president, and a fully grown Mattie is looking back on how, at fourteen, she hired a U.S. marshal (Rooster) to track the killer into Indian territory, to catch him and exact her revenge. Her supreme confidence in the righteousness of her cause burns even brighter than does Wayne’s and his cohort for the cause in Vietnam. Mattie’s mission, too, is one of justice in the territory, as it were.

“I was just fourteen years old,” goes the novel’s second sentence, “when a coward going by the name of Tom Chaney shot my father down in the street in Fort Smith, Arkansas and robbed him of his life and his horse and $150 in cash money plus two California gold pieces that he carried in his trouser band.” The year is never named, but a history buff with basic math skills can figure it out—1878. Fifty years have passed since the murder, Hoover has been elected president, and a fully grown Mattie is looking back on how, at fourteen, she hired a U.S. marshal (Rooster) to track the killer into Indian territory, to catch him and exact her revenge. Her supreme confidence in the righteousness of her cause burns even brighter than does Wayne’s and his cohort for the cause in Vietnam. Mattie’s mission, too, is one of justice in the territory, as it were.

We were walking, my wife and I, from our parking space to the door of the Beto O’Rourke campaign office in south Dallas on the evening of its official opening celebration. Beto, running to unseat Ted Cruz in the US Senate, was scheduled to appear. Even before we got to the door, we could see a crowd of people around it and more like us converging from their own parking spaces. Coming up alongside us was Daniel, who I recognized from numerous other political events.

We were walking, my wife and I, from our parking space to the door of the Beto O’Rourke campaign office in south Dallas on the evening of its official opening celebration. Beto, running to unseat Ted Cruz in the US Senate, was scheduled to appear. Even before we got to the door, we could see a crowd of people around it and more like us converging from their own parking spaces. Coming up alongside us was Daniel, who I recognized from numerous other political events. Lawrence Wright’s book, God Save Texas, came out last spring, and I read it not long after with great pleasure. Wright is a staff writer for The New Yorker. He won a Pulitzer for his book on 9-11, The Looming Tower. A baby boomer, Wright grew up in Dallas and has lived in Austin since 1980. In this latest book, he covers all the important aspects of his home state– its cities, its regions, its history and music– but his main topic is politics. Texas politics have always had a “burlesque side,” Wright acknowledges, a “recurrent crop of crackpots and ideologues,” and now it’s as bad as it’s ever been. The problem is that the state’s size renders it especially influential. “Texas has nurtured an immature political culture that has done terrible damage to the state and to the nation,” Wright believes.

Lawrence Wright’s book, God Save Texas, came out last spring, and I read it not long after with great pleasure. Wright is a staff writer for The New Yorker. He won a Pulitzer for his book on 9-11, The Looming Tower. A baby boomer, Wright grew up in Dallas and has lived in Austin since 1980. In this latest book, he covers all the important aspects of his home state– its cities, its regions, its history and music– but his main topic is politics. Texas politics have always had a “burlesque side,” Wright acknowledges, a “recurrent crop of crackpots and ideologues,” and now it’s as bad as it’s ever been. The problem is that the state’s size renders it especially influential. “Texas has nurtured an immature political culture that has done terrible damage to the state and to the nation,” Wright believes. What was Beto like? What did he do and say? I won’t belabor this much further. You can get a look at him and hear him speak in any number of settings—the video links on Youtube are legion. His answer to a town hall question about kneeling during the anthem has recently gone viral, for whatever that’s worth. This was my third time to see him live, however. The first time was on a corner at a march in support of immigrants, before many knew who he was. The second time was well into the race, in the Texas Theater, the old movie house where they arrested Oswald, and there was a line down the block to get in. So how did this third time compare?

What was Beto like? What did he do and say? I won’t belabor this much further. You can get a look at him and hear him speak in any number of settings—the video links on Youtube are legion. His answer to a town hall question about kneeling during the anthem has recently gone viral, for whatever that’s worth. This was my third time to see him live, however. The first time was on a corner at a march in support of immigrants, before many knew who he was. The second time was well into the race, in the Texas Theater, the old movie house where they arrested Oswald, and there was a line down the block to get in. So how did this third time compare?